India’s lawless financial capitalism fosters a culture of scams

Cheered on by the state, it has infused an alarming disregard for ethical conduct and public accountability.

Starting in early 1989, the Indian stock market index, the Sensex, began scaling new heights. The spectacular rise through April 1992 was a puzzle: politics was in chaos, the economy was troubled, and yet the Sensex kept climbing, in a near-vertical ascent towards the end.

That episode, known since as the “Harshad Mehta scam”, is largely forgotten, and certainly dismissed for contemporary relevance because it was the creature of a unique moment. However, scams have recurred all too frequently and today are often a way of doing business. The costs to India’s economy and society have been large.

Most damagingly, scams have centred around malpractices in corporate governance: owners and promoters of companies have defrauded investors to enrich themselves. The Indian state, although armed with administrative and regulatory tools, has failed in its duty to safeguard the sanctity of the law. That state failure has caused an erosion of trust, the fundamental glue of social and market transactions. As Judge Arthur Engoron explained recently in State of New York vs Donald Trump, the legal system must maintain the “integrity of the marketplace” so as to ensure that transactions are “honest” and adhere to “the standards of fairness”. Integrity, honesty, and fairness may seem alien, even quaint, in a materialistic society. But as another US judge argued in a related matter, “the state has its own interest” in these moral values. Markets, the judges were saying, fail to achieve their economic and social purpose when the state does not rein in greed. As the great free-marketeer Adam Smith emphasised more than two centuries ago, markets fail where “avarice” vanquishes the moral virtues of prudence and fairness.

Indian observers have dismissed scams as entertaining exceptions orchestrated by socially deviant individuals operating at the edges of normalcy. With time though, the edgy behaviour of some has created an authorising environment for many. The deviant has become normal. Today, scamming is commonplace. Scams are even celebrated for the hyper-individuality they showcase. Lawless financial capitalism—cheered on by the state—has infused broader disregard for moral norms and public accountability. As Professor Partha Dasgupta explains, when everyone expects others will cheat, everyone cheats to stay ahead of other cheaters.

Harshad Mehta’s long shadow

The Harshad Mehta scam remains relevant because it warned of the dangers of unregulated capitalism. That warning got buried in the narrative of bountiful economic liberalisation. The lesson: beware extravagant narratives.

The stock market began its inexplicable rise in March 1990 even as India hurtled towards international bankruptcy. The 36-year-old Mehta’s mystique grew, especially when he moved from a modest home in Vikhroli to a seafront property in Worli. Allegedly valued at Rs.10 crore at the time, the new property had a nine-hole putting green, a Japanese garden, and parking for Mehta’s many luxury cars. In May 1990, the IMF wrote approvingly of India’s “booming stock market” for moderating the risks of plummeting foreign exchange reserves. In August 1990, Citibank India analysts hailed India’s economic prospects. Their reason for optimism: “India’s capital markets have come of age.” They self-consciously referred to rumours that financial institutions such as Citibank India were funding the market’s bizarre rise. The analysts rejected such insinuations, saying they found “no evidence” for it.

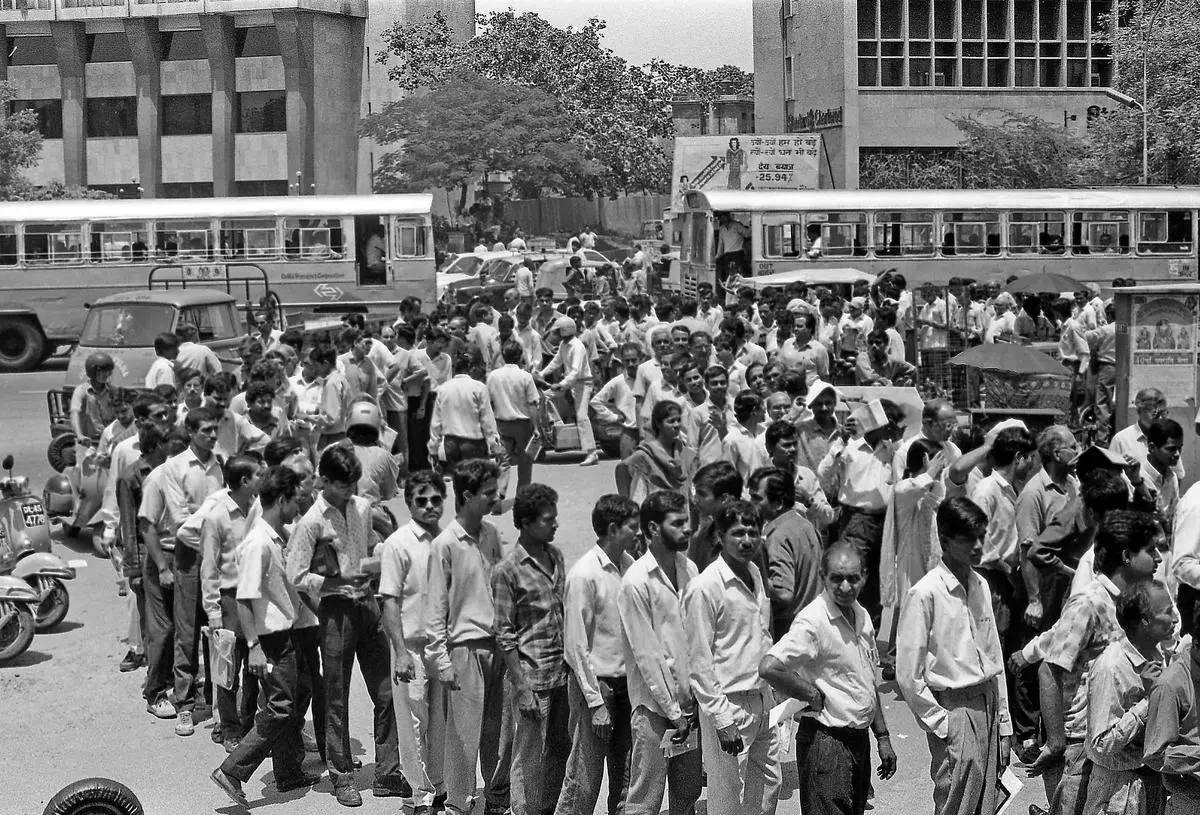

Stock market investors wait in long queues in front of bank counters with share applications at Parliament Street in New Delhi after the Harshad Mehta scam was revealed in 1992. | Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

The narrative of success got a boost in June-July 1991 when a new government led by Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao and Finance Minister Manmohan Singh dismantled import and industrial controls. This was a pivotal moment. Absent the needed human capital, gender equality, and functioning cities, the intended (and hoped for) boost to manufacturing never materialised. Instead, lawless financial capitalism took root.

Financial regulators were clueless about the reasons for and Harshad Mehta’s role in the market’s rise. The Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) investigated Mehta’s operations. The Income Tax Department raided his home and office in early 1992. The taxmen were apparently looking for a link to a Dubai-based underworld don but came away empty-handed. S.A. Dave, chairman of the Unit Trust of India (a government-owned mutual fund), referred darkly to hot money inflows. And Reserve Bank Governor S. Venkitaramanan called a meeting of financial institutions.

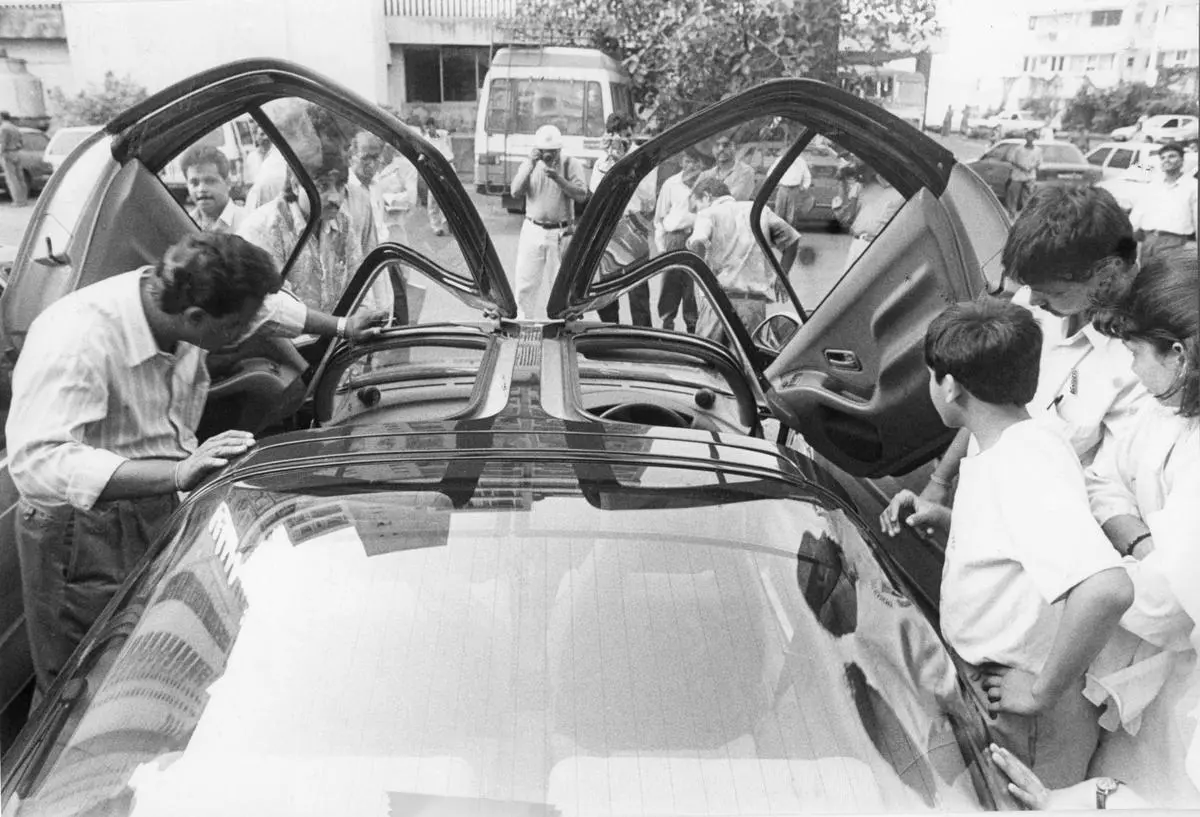

Potential buyers examine a Toyota Sera belonging to Harshad Mehta at his residence in Mumbai. The 18 cars Mehta owned were auctioned by a Special Court. | Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

By February 1992, the share price of Associated Cement Corporation (ACC) had risen to Rs.4,500, up from Rs.350 a year earlier; the broader market index, the Sensex, had risen to 2,300, up from 1,000 over the same period. Financial Times helpfully suggested that the Finance Minister’s reforms were causing the market’s rise. Then a madness set in: in just over two months through late April, the ACC share price more than doubled to Rs.11,500 and the Sensex almost doubled to 4,500.

Sure enough, it came crashing down. A year later, the Sensex had fallen to about 2,000. Indian capital markets had not magically transformed (as Citibank analysts had proposed); nor were markets foreseeing the benefits of reforms, as Financial Times claimed. The IMF’s wishful thinking notwithstanding, the market boom did not avert an old-fashioned IMF bailout.

Under the cover of extravagant narratives, Mehta used interest-free funds from state-owned banks to buy chosen stocks. Post-mortems by various watchdogs had the flavour of a judge’s decision to dismiss the charges against Jessica Lal’s murderers. As The Times of India then reported: “No one killed Jessica Lal.” In the Harshad Mehta scam, the management and executive board of State Bank of India faced no accountability even though that premier bank had, in effect, “lent” Mehta Rs.500 crore interest-free to play the market. Officials rallied behind the Reserve Bank, declaring it could not detect the scam because it lacked the digital capability to track Mehta’s transactions in real time. This was a cop-out. The Reserve Bank had over three years—and the obligation—to inspect banks for unusual activity. Charitably, it missed the fraud in plain sight, a feat that became a habit.

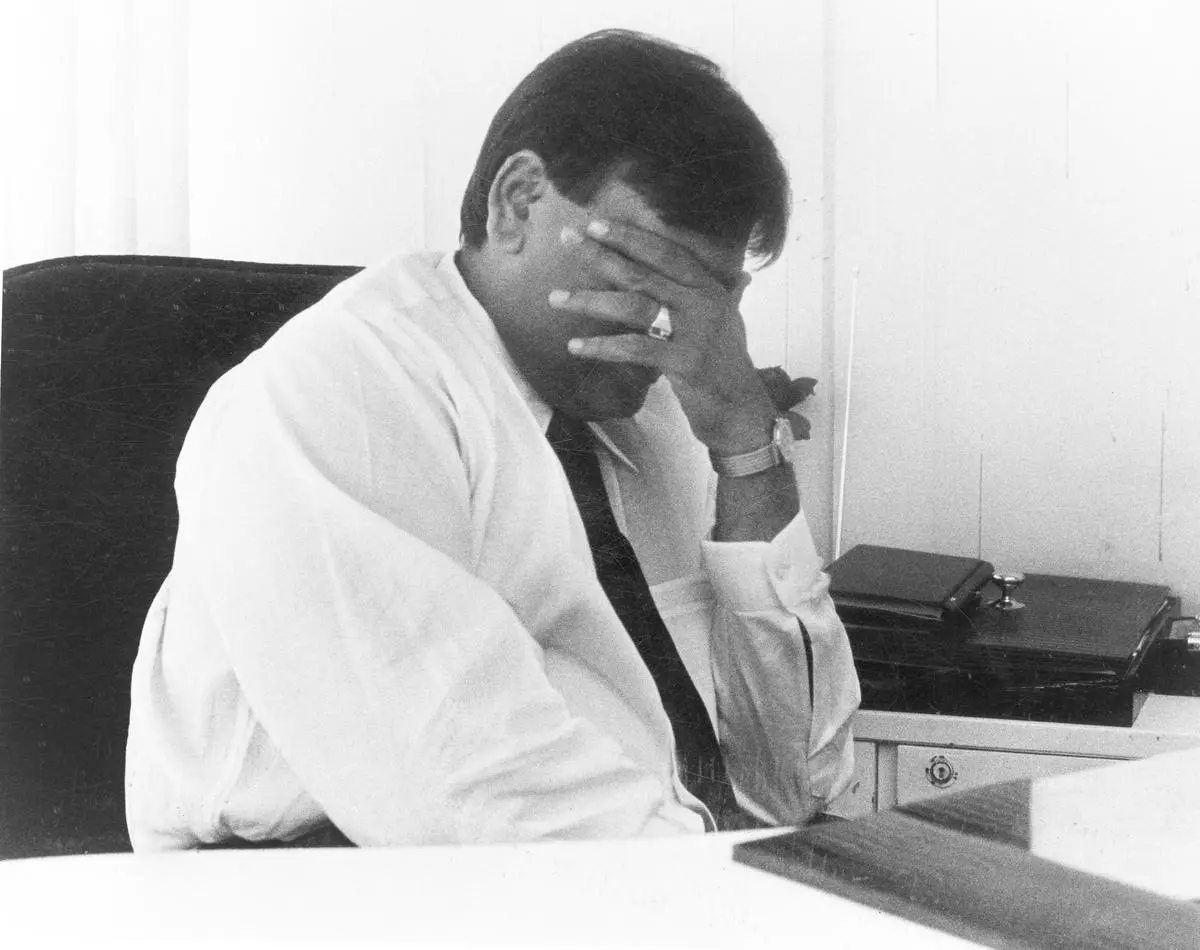

Harshad Mehta seen during questioning regarding the stock market scam. | Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

Mehta died an early death. The Income Tax Department still hounds his wife for taxes due. But he became a folk hero. This was the age of Gordon Gecko. Greed was good. The author Pankaj Mishra, writing his first book, a travelogue, had a travelling companion on a train journey, a Mr Goenka. “People consider Harshad Mehta corrupt,” Goenka said. “Why is he corrupt? Because he made a lot of money? I think he is a genius. I say even if he is corrupt, he is inspiring young people.” Mehta’s modus operandi became obsolete. His larger-than-life legacy lived on.

Ketan Parekh charts the way

Harshad Mehta inspired a notable young man: Ketan Parekh. Born in 1963, Parekh once worked for Mehta and came into his own as the new “big bull” around 1998. Less of a loudmouth than his former boss, Parekh rode the global boom in information technology stocks. Amid the new get-rich-quick narrative, he pushed up the stock prices of obscure information technology and communication companies. These companies had low “floating stocks”, meaning their promoters held much of the equity, leaving only a small portion of the stock ownership to trade. In those thinly traded markets, Parekh pushed prices up and thus seduced institutional investors into buying the stock believing it would keep appreciating. Even after the global boom ended in February 2000—at which time the Sensex briefly crossed a high of 6,000 in intra-day trading—Parekh successfully pushed up prices of his targeted stocks. His run ended only in early March 2001 when a so-called “bear cartel” crashed the prices of his stocks. Parekh blazed trails that others traverse to this day. He exposed embarrassing holes in India’s corporate governance: owners and promoters could defraud investors easily. In a memorable transaction early in his career, he coordinated with Gautam Adani’s officials to help run up the stock price of Adani’s flagship company. He revealed that technologically sophisticated regulatory safeguards were toothless without vigilant human regulators. Above all, he pioneered the use of Mauritius (and other tax havens) to launder ill-gotten wealth.

In perhaps the only documented case, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) found evidence that, between October 1999 and March 2001, Gautam Adani’s officials participated in engineering surges in the stock price of Adani Exports, the precursor to Adani Enterprises. They did so with Parekh and other brokers. The associated parties engaged in so-called “circular trading”, which denotes synchronised buy and sell orders at successively higher prices. As the SEBI examiner noted, other than those circular trades, “there were hardly any genuine volumes in the scrip”. The synchronisation gave the appearance of large trading volumes and ensured that the traded prices were recorded as the new market prices. Even today, despite alleged safeguards in electronic trading, scammers manipulate stock prices through circular trading/synchronisation of orders.

To fund his market moves, Parekh used—Harshad Mehta style—weak links in the domestic banking system, in his case urban cooperative banks, especially the Madhavpura Mercantile Cooperative Bank. But Parekh would have been a forgotten scammer if he had not identified the Mauritius route to launder vast sums.

Source / Credits / Reference: FrontlineRef URL: https://tinyurl.com/bdhkhjam

Back to blogs

Blog Views : 554 02-12-2023